Audition (1999) Still Cuts Deep: Revisiting J-Horror’s Haunting Take on Power and Male Fantasy

The J-horror classic is both one of the most disturbing films ever made and one of the most thoughtful deconstructions of male fantasy

Warning: this article contains spoilers for the movie discussed and carries a trigger warning for discussions of sexual violence. This analysis is part of an ongoing film analysis project, the Madonna-Monster Project, which you can read about here.

DIRECTOR: Takashi Miike

SCREENPLAY: Ryû Murakami, Daisuke Tengan

STARRING: Ryô Ishibashi, Eihi Shiina, Tetsu Sawaki

LANGUAGE: Japanese

RUN TIME: 1hr 55mins

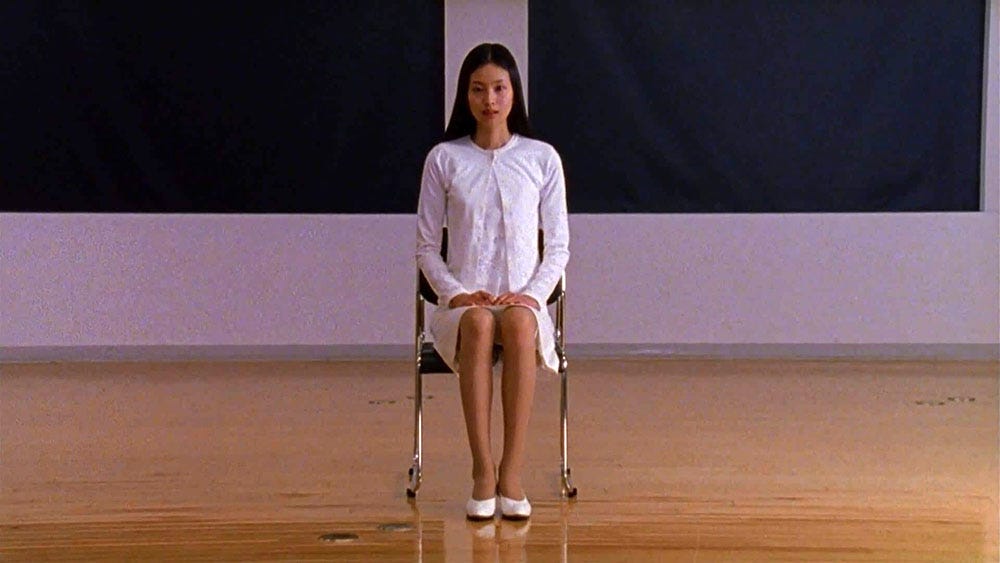

Eihi Shiina plays Asami Yamazaki in the classic 1999 J-horror Audition. Distributed by Art Port.

INTRODUCTION

The first time I watched Audition (1999) was out of morbid curiosity. I’d seen it top multiple lists as one of the best and most disturbing horror movies ever made. The movie shot to international acclaim alongside other Japanese horrors like Ringu (1998), Ju-on (2000), and Battle Royale (2000). It’s since been touted as one of the major influences behind extreme ‘torture porn’ movies created by directors like Eli Roth (of the Hostel franchise) and for good reason. The last thirty or so minutes feature some of the most brutal, difficult-to-watch imagery committed to camera. A man’s foot is dismembered with a wire, and needles are slowly inserted into his torso and underneath his eyes by a woman chanting “kiri kiri kiri” with childlike glee. But while rewatching it, I became fascinated by the movie’s examination of male fantasy and gender dynamics.

‘Audition’ is a slow burn that follows Aoyama (Ryô Ishibashi), a widowed film producer and single father who, after being urged by his son Shige (Tetsu Sawaki) and his colleague and friend Yoshikawa (Jun Kunimura), decides to audition women for a fake movie to find a new suitable wife. He becomes enraptured by a demure, beautiful ex-ballerina named Asami (Eihi Shiina), but as he digs into her mysterious past, he realises that she is not who she seems.

The film is based on Ryu Murakami’s 1997 novel of the same name. It starts as a romance. As it continues, it blends romantic movie tropes with sinister undertones to create an off-kilter experience that feels like a tense deconstruction of the romance genre. It feels like an early critique of the same issue in romance films that the Buscemi Test was designed to poke fun at. The test, often used by my favourite feminist film podcast The Bechdal Cast, looks at a character’s actions in a romantic movie like say, The Notebook (2004) in which lead character Noah threatens to end his life on a ferris wheel unless Allie (Rachel McAdams) agrees to go out with him, and imagines that instead of being played by Ryan Gosling, Noah was played by someone, er…less conventionally attractive like Steve Buscemi. Is the result creepy rather than romantic? And if it is, that indicates the “romantic” gesture is actually disturbing.

The movie arguably presents both Asami and Aoyama’s actions through this lens, with different interpretations of the results. Some have argued that the film is misogynistic in the way it presents women outside of Asami as throwaway characters. But I’m inclined to agree with the feminist interpretation that sees the movie as a critique of the oppressive and objectifying standards imposed on Japanese women.

Asami’s sadism is presented as revenge for years of being mistreated and abused by men. For this reason, I’ve chosen to analyse her as part of my ongoing project of mapping a feminist analytical lens onto female horror characters, which I’ve called the Madonna-Monster complex. This refers to women characters who are repressed into idealised gendered roles and representations of womanhood, or “Madonna” figures, unleashing their pent-up anger and frustration in the form of a monster.

A lot of attention has been given to the gratuitous violence towards the end, and for good reason. The final scenes are borderline unwatchable, and I warn anyone with a weak stomach to steer clear. But for those able to stomach it, ‘Audition’ offers a thoughtful examination of how harmful, unrealistic, and misogynistic male fantasies can be for the women subjected to them.

SUMMARY

‘Audition’ opens with a death. Aoyama, a widowed film producer, loses his wife, Ryoko (Miyuki Matsuda), to an unnamed illness. Years later, encouraged by his teenage son Shige and his business partner Yoshikawa, Aoyama begins to consider remarriage. The pair stage a fake film audition to help Aoyama find a new wife. Specifically, a young, obedient, classically trained woman. During a montage of questionable auditions, where women are asked invasive questions and made to undress, one applicant stands out: Asami, a quiet ex-ballerina who claims to have quit dancing due to injury.

Asami Yamazaki enraptures Aoyama during her audition. Distributed by Art Port.

Yoshikawa is immediately wary. None of Asami’s references can be contacted, and some have mysteriously vanished. “She has no boyfriend, and she fell into our trap,” he says. “Isn’t it too good to be true?” But Aoyama, captivated by her beauty and submissive demeanour, ignores the warnings. He begins dating her, unaware that she sits waiting for his calls in an empty apartment with a tied human-shaped sack in the background.

Despite multiple red flags, Aoyama plans a weekend away with Asami, intending to propose. The night of the proposal, she reveals scars from childhood abuse and accepts, pleading, “Please love me. Only me.” But when Aoyama wakes, she’s gone. His search for her leads him to a dance studio where a sinister, limbless piano teacher admits to burning her legs as punishment. Aoyama tries the restaurant she said she worked at, but finds that it has been boarded up for over a year. A local tells him the owner was murdered and found chopped to pieces, but when the police put her body parts together, they found extra fingers, a second tongue, and a third ear.

Meanwhile, someone breaks into Aoyama’s home. He returns, drinks whiskey that has been drugged without his knowledge, and collapses. In a dreamlike hallucination, he relives conversations with Asami and learns of the abuse she suffered from her uncle and stepfather. He has a vision of Asami’s house and sees a dirty man whose feet have been amputated emerge from the sack begging for food. Asami vomits into a dog bowl and feeds it to the man.

He awakens paralysed in his home. Asami is there wearing gloves and an apron. She accuses him of using the audition as a ploy for sex, declaring, “All men are the same.” She also threatens her son, saying that as Aoyama had promised to love only her his love for his son was unacceptable. She tortures him by inserting needles into his torso and beneath his eyes, repeating the phrase kiri kiri kiri (“deeper, deeper”), before cutting off his foot with a wire.

As she prepares to sever the second, Shige returns home. Aoyama wakes up back at the hotel with Asami at his side shortly after accepting his proposal. She says to him, “Among the girls who auditioned for this role, I am the luckiest one. Because I am the real heroine.” But this is revealed to be another hallucination. As he comes to, Shige knocks Asami down the stairs, breaking her neck. As she dies, an earlier speech of hers to Aoyama replays, telling him that she is lonely and looking for someone to understand and accept her as she truly is.

MALE FANTASY AND ROLE REVERSAL

‘Audition’ reinforces that Aoyama’s fantasy woman is both unrealistic and self-serving. He prioritises superficial traits like youth, beauty, and obedience, while ignoring glaring warning signs because he is too enchanted by Asami’s soft-spoken persona, her lowered gaze, and her tragic elegance which make her a Madonna figure molded by his fantasy.

It’s difficult to feel sorry for him once its revealed that Asami deceived him because he has also deceived her. The audition sequence is an uncomfortable watch because of the lack of informed consent underscoring it. One has to question whether any of the women would have agreed to talk to Aoyama, let alone take off their clothes, perform for him, and give him their details had they known his true motives. Every woman Aoyama encounters is objectified. And an earlier conversation with Yoshikawa, in which they speak disparagingly about modern Japanese women, reveals that his views are reflective of broader societal attitudes.

Asami sits by the telephone waiting for Aoyama to call in a room with a mysterious sack sitting in the corner. Distributed by Art Port.

This is also apparent just before the auditions begin. Yoshikawa tells Aoyama that the woman they select should not be the woman who would get the lead role were they to actually produce the movie. She should rather be a woman who would pass the first screening but not the second. It’s a telling moment that speaks to one of the many contradictions the fantasy woman must adhere to. She must be smart and accomplished, but not enough that her ambition and skill pose a threat.

In this context, Asami’s actions serve as a pointed retaliation against this misogyny. I’ve mentioned earlier that in horror, a monster transformation allows women to subvert power dynamics through role reversal. This power reversal is made apparent in the movie. Asami is clearly playing a role. She flatters him constantly, even mentioning that she never expected to get the lead role. She tells Aoyama she was surprised to receive his call even though she had sat waiting by the phone for days. Through telling him what he wants to hear and showing him her burn scars as a way of feigning intimacy and vulnerability, she uses the Madonna archetype to set her own trap.

And her monster transformation allows her to gain power over the men who once used and abused her. She accuses Aoyama of using her like an object, and she’s not wrong. Her reaction is certainly disproportionate, but that’s because she isn’t just reacting to Aoyama. She’s reacting to years of being objectified, abused, and discarded by men. In this context, I found it rather telling that her long black hair and all-white ensembles make her resemble onryō, malevolent female spirits in Japanese culture who seek revenge on all they encounter (and have been the inspiration for a slew of J-horrors including ‘Ringu’ and ‘Ju-on’)

Asami is neither solely a villain nor victim. She embodies rage suppressed by decades of objectification and pain. Her sadism is a distorted reclamation of power and a monstrous response to being idealised, silenced, and used.